You have to ask, how can UK governments keep getting it so successfully wrong?

With 13 major U-turns under its belt and counting, this government has realised its inexperience is costing it voters. The blame - at least a good portion - has landed on the record number of special advisors (SPADs) it has leant on for the lack of Civil Service feasibility testing and public acceptance before announcing measures.

Special advisers are political appointees who do what civil servants cannot: they give partisan advice, brief journalists, coordinate with party HQ and act as attack dogs when required.

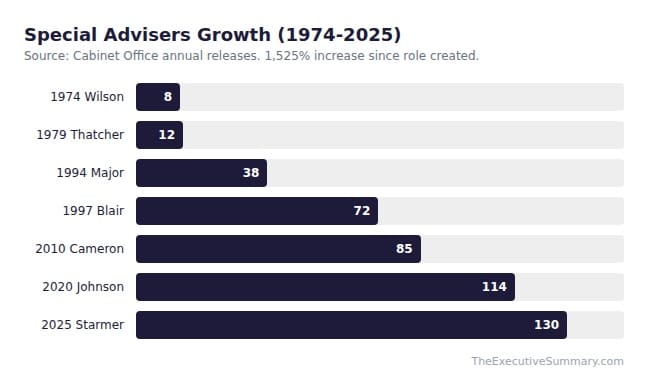

Churchill had no special advisers. When Harold Wilson created the role in 1974, he appointed eight. Fifty years later, Keir Starmer employs 130 officially. Westminster insiders suggest the real number is closer to 160.

Wilson created the role so ministers would have trusted staff who understood their political objectives rather than just the machinery of government. The explosion in numbers reflects the explosion in demand for reactive capacity.

Before SPAD-creep, ministers relied on their permanent secretary and senior officials for policy advice. In 2015, the SPAD code was amended to let advisers convey ministerial instructions to officials. Previously they could only advise, but now they could command, which changed the balance of power.

This has made life hard for Civil Servants, especially when many SPADs are hired straight after leaving the Student Union bar - usually the Oxbridge one - with little or no experience of large organisations, let alone government.

It is akin to giving a non-driver the keys to a Bugatti and expecting it all to be fine.

It is akin to giving a non-driver the keys to a Bugatti and expecting it all to be fine.

One Permanent Secretary admitted that good SPADs are now often more influential than junior ministers. At the same time, the people who know how government delivers have been pushed to the margins by people who know how politics works.

A senior insider recently told me: "The only difference between The Thick of It and real government work is in The Thick of It, they weren't all running around saying: 'It's like being in an episode of The Thick of It'."

No Interview Required

There is no official route to becoming a SPAD. They are employed by the state, not political parties, but are appointed entirely through political discretion - often through who you know or who worked on a campaign.

This is unlike other government hiring procedures. Each SPAD is chosen by a minister, approved by the Prime Minister and formally contracted by the Cabinet Office. They are usually hired on fixed-term contracts as temporary civil servants, paid from public funds and exempt from the requirement to be politically impartial.

At a time when most organisations are being pressured to comply with a thousand regulations, the government engine is playing economic roulette with interns.

Are SPADs Behind the Cockups?

It would be over simplistic to say so, but as their numbers and influence rises, so does their cockup contribution.

In large organisations, cockups are a team effort - and in government even more so.

The easy answer is that SPADs and their politicians have become worse. The accurate answer is that the job of being a successful minister has become impossible - and only a certain type of person would ever stand up to do it.

This is because three forces have converged to create an environment where holding any position in government, for any length of time, carries exponentially higher risks than it did a generation ago:

The SPAD Explosion

Tony Blair nearly doubled the SPAD count overnight, from 38 to 72.

Notably, this happened at the arrival of 24-hour news. Sky News launched in 1989. BBC News 24 followed in 1997. The news cycle had accelerated from daily to hourly and government needed the staff to keep pace.

Scandal Growth: The Cockupometer

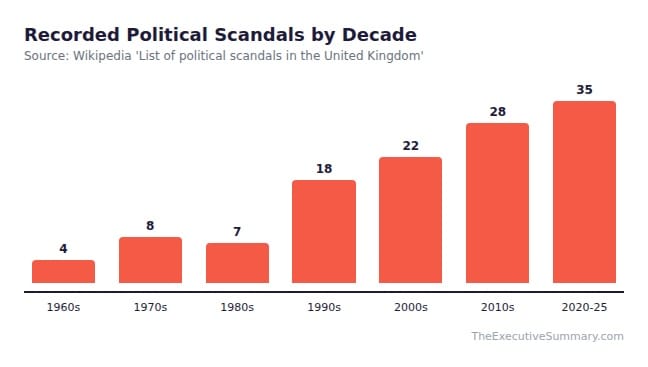

You can see the number of political scandals then sharply rose. Perhaps not because the number of cockups had changed, but the number of reported scandals had.

In the 1960s there were four. By the 2020s there are 35 and counting. The 1990s mark the turning point when scandals more than doubled, exactly when 24-hour news arrived.

Media Amplification

The word 'crisis' appears on almost every BBC News ticker today. So have politicians become worse? Or is media amplifying behaviour that would previously have gone unrecorded?

When you consider the impact of growing media exposure to the same political story, the impact of cockups on the general public would be much higher. In other words, social media, memes and shorts amplify the cockup and the pressure on officials.

Now I did these sums while sitting in the pub, so you can probably find some inaccuracies, but roughly speaking, there is far more exposure to a single political scandal than there was 50 years ago.

In 1963, news of the Profumo affair reached you twice a day: once in the morning paper, once on the evening news. The same scandal today would hit you 50 to 100 times across news sites, social feeds, push notifications, group chats, memes, parody accounts and TikTok remixes.

| Era | Primary News Sources | Daily Exposures to Same Story |

|---|---|---|

| 1960s | Morning paper, evening TV | 2 |

| 1970s | Paper, lunchtime + evening TV | 4 |

| 1980s | Paper, breakfast TV, lunch, evening | 5 |

| 1990s | Paper + 24hr news (multiple check-ins) | 10 |

| 2000s | All above + websites + email alerts | 20 |

| 2010s | All above + social feeds + shares | 40 |

| 2020s | All above + push notifications + memes + TikTok | 75 |

Constructed index. Supporting research: 205 phone checks/day (Reviews.org 2024); 237 notifications/day for teens (Common Sense Media 2023); 61 minutes daily news consumption, 47% via social media (Ofcom 2025).

Speaking from experience of having worked in media, it is much easier to control a story when there are few channels covering it. When all the channels cover it, there is little chance of containment.

Enter - the SPAD.

The Rise of the SPAD

This leads to knee-jerk reactions and fast - often wrong - decisions with poor communication controls across large organisations. It is a recipe for disaster, but amplifies the need for SPADs. More SPADs mean more people monitoring the news cycle, shaping narratives and preparing counter-attacks around the clock.

It is a reactive game - and once you start leading with reactive measures, it is almost impossible to stop. Much of this communication is out of sync with the Civil Service, but it's s vicious cycle.

The SPAD gets a policy concept launched. The media covers it. The SPAD reacts, announces reaction and the media covers it. And so it goes on, but in faster cycles than ever.

Innocent Advisors

Can we then blame the SPAD? Not really. But there is systematic fault with those appointing them.

If you were offered the SPAD role as a grad through someone you know, you'd think very hard before turning it down. What an opportunity - to see how government works and affect change.

Would you say no to the power to influence policy if you were in that position? If you were an ambitious youngster, again, it would be hard not to.

The SPADs didn't set this system up.

But should SPADs have so much unregulated influence with such little governance?

No. And this is the problem.

With almost every industry under more pressure to comply, those informing policy for government are themselves ungoverned. They sit outside the org chart with little accountability for mistakes.

This has to change or you can expect the cockups to keep rising.

This Newsletter was sponsored by

The Proposition: